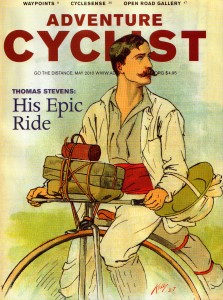

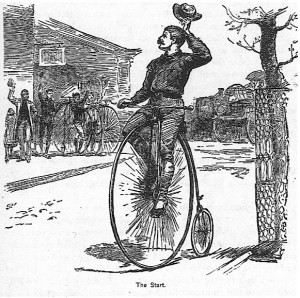

Thomas Stevens was the first person to circle the globe by bicycle. He rode a large-wheeled Ordinary, also known as a penny-farthing, from April 1884 to December 1886. He carried a handlebar bag with essentials like socks, a spare shirt and a rain jacket that was also his tent. His journey took him across Europe, through Iran and into Afghanistan, across India, China and Japan, before he returned by steamer to San Francisco.

Thomas Stevens was the first person to circle the globe by bicycle. He rode a large-wheeled Ordinary, also known as a penny-farthing, from April 1884 to December 1886. He carried a handlebar bag with essentials like socks, a spare shirt and a rain jacket that was also his tent. His journey took him across Europe, through Iran and into Afghanistan, across India, China and Japan, before he returned by steamer to San Francisco.

Some excerpts from his book Around The World On A Bicycle.

[…]

CHAPTER XIX.

THROUGH JAPAN.

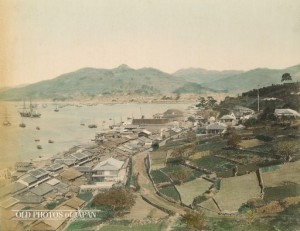

An uneventful run of two days, and the Yokohama Maru steams into the beautiful harbor of Nagasaki. The change from the filth of a Chinese city [Shanghai] to Nagasaki, clean as if it had all just been newly scoured and varnished, is something delightful. One gets a favorable impression of the Japs right away; much more so, doubtless, by coming direct from China than in any other way. […]

An uneventful run of two days, and the Yokohama Maru steams into the beautiful harbor of Nagasaki. The change from the filth of a Chinese city [Shanghai] to Nagasaki, clean as if it had all just been newly scoured and varnished, is something delightful. One gets a favorable impression of the Japs right away; much more so, doubtless, by coming direct from China than in any other way. […]

Having duly supplied myself with Japanese paper-money—ten, five, and one yen notes; fractional currency of fifty, twenty, and ten sen notes, besides copper sen for tea and fruit at road-side teahouses, on Tuesday morning, November 23d [1886], I start on my journey of eight hundred miles through lovely Nippon to Yokohama.

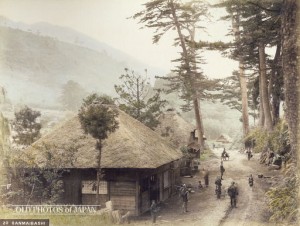

[…] A showery night has made the roads a trifle muddy. Through the long, neat-looking streets of Nagasaki, into a winding road, past crowded hill-side cemeteries, adorned with queer stunted trees and quaint designs in flowers, I ride, followed by wondering eyes and a running fire of curious comments from the Japs.

[…] A showery night has made the roads a trifle muddy. Through the long, neat-looking streets of Nagasaki, into a winding road, past crowded hill-side cemeteries, adorned with queer stunted trees and quaint designs in flowers, I ride, followed by wondering eyes and a running fire of curious comments from the Japs.

Nagasaki lies at the shoreward base of a range of hills, over a pass called the Himi-toge, which my road climbs immediately upon leaving the city. A good road is maintained over the pass, and an office established there to collect toll from travellers and people bringing produce into Nagasaki. The aged and polite toll-collector smiles and bows at me as I trundle innocently past his sentry-box-like office up the steep incline, hoping that I may take the hint and spare him the necessity of telling me the nature of his duty. My inexperience of Japanese tolls and roads, however, renders his politeness inoperative, and, after allowing me to get past, duty compels him to issue forth and explain. A wooden ticket containing Japanese characters is given me in exchange for a few tiny coins. This I fancy to be a passport for another toll-place higher up. Subsequently, however, I learn it to be a return ticket, the old toll-keeper very naturally thinking I would return, by and by, to Nagasaki.

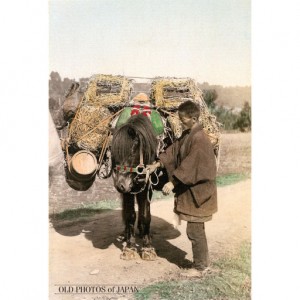

Ponies and buffaloes, laden with baskets of rice, fodder, firewood, and various agricultural products, are encountered on the pass, in charge of Japanese rustics in broad bamboo-hats, red blankets, bare legs, and straw sandals, who lead their charges by long halter-ropes. Both horses and buffaloes are shod with shoes of the same unsubstantial material as the men. When the Japanese traveller sets out on a journey, he provides himself with a new pair of straw sandals; these last him for a tramp of from ten to twenty miles, according to the nature of the road. When worn out, his foot-gear may be readily renewed at any village for a mere song. The same may be said of his horse or buffalo, although several extra shoes are generally carried along in case of need.

Ponies and buffaloes, laden with baskets of rice, fodder, firewood, and various agricultural products, are encountered on the pass, in charge of Japanese rustics in broad bamboo-hats, red blankets, bare legs, and straw sandals, who lead their charges by long halter-ropes. Both horses and buffaloes are shod with shoes of the same unsubstantial material as the men. When the Japanese traveller sets out on a journey, he provides himself with a new pair of straw sandals; these last him for a tramp of from ten to twenty miles, according to the nature of the road. When worn out, his foot-gear may be readily renewed at any village for a mere song. The same may be said of his horse or buffalo, although several extra shoes are generally carried along in case of need.

The summit of the pass is distinguished by a very deep cutting through the ridge rock of the mountain, and a series of successive sharp turns back and forth along narrow-terraced gardens and fields bring the road down into the valley of a clear little stream, called the Himi-gawa. Smooth, hard roads follow along this purling rivulet, now and then crossing it on a stone or wooden bridge. A small estuary, reaching inland like a big bite out of a cake, is passed, and the pretty little village of Yagami reached for dinner.  The eating-house, like nearly all Japanese eating-places, is neat and cleanly, the brown wood-work being fairly polished bright from floor to ceiling.

The eating-house, like nearly all Japanese eating-places, is neat and cleanly, the brown wood-work being fairly polished bright from floor to ceiling.

Sitting down on the edge of the raised floor, I am approached by the landlady, who kneels down and bows her forehead to the floor. […]

Fish and rice (sakana and meshi) are the most readily obtainable things to eat at a Japanese hotel, and often form the only bill of fare. […]

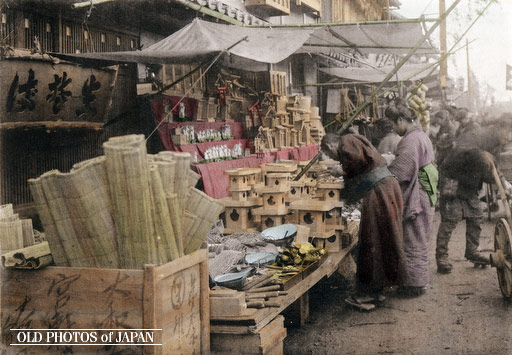

Every tea-house along the road is made doubly attractive by prettily dressed attendants-smiling girls who come out and invite passing travellers to rest and buy tea and refreshments. Their solicitations are chiefly winsome smiles and polite bows and the cheerful greeting “O-ai-o” (the Japanese “how do you do”). A tiny teapot, no larger than t hose the little girls at home play at “keeping house” with, and shell-like cup to match, is brought on a lacquered tray and placed before one, with charming grace, if a halt is made at one of these tea-houses. Persimmons, sweets, cakes, and various tid-bits are temptingly arrayed on the sloping stand in front. The most trifling purchase is rewarded with an exhibition of good-nature and politeness worth many times the money.

hose the little girls at home play at “keeping house” with, and shell-like cup to match, is brought on a lacquered tray and placed before one, with charming grace, if a halt is made at one of these tea-houses. Persimmons, sweets, cakes, and various tid-bits are temptingly arrayed on the sloping stand in front. The most trifling purchase is rewarded with an exhibition of good-nature and politeness worth many times the money.

[…]

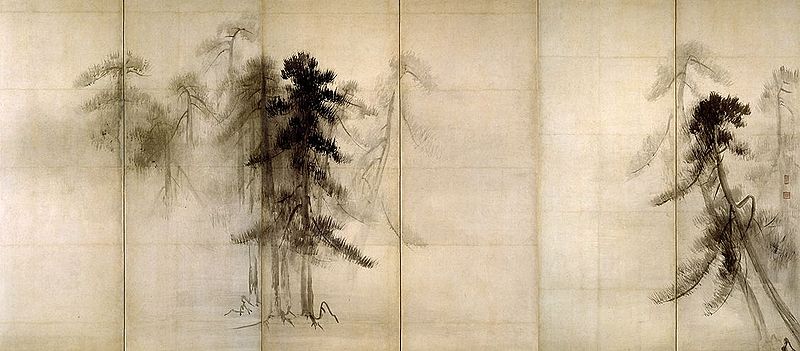

A very good road, with an avenue of fine spreading conifers of some kind, leads out  of Omura. To the left is the bay of Omura, closely skirted at times by the road. At one place is observed an inland temple, connected with the mainland by a causeway of rough rock. The little island is covered with dark pines and jagged rocks, amid which the Japs have perched their shrine and erected a temple. Both the Chinese and Japs seem fond of selecting the most romantic spots for their worship and the erection of religious edifices.

of Omura. To the left is the bay of Omura, closely skirted at times by the road. At one place is observed an inland temple, connected with the mainland by a causeway of rough rock. The little island is covered with dark pines and jagged rocks, amid which the Japs have perched their shrine and erected a temple. Both the Chinese and Japs seem fond of selecting the most romantic spots for their worship and the erection of religious edifices.

The day is warm, and a heavy shower during the night has made the road heavy in places, although much of it is clean gravel that is not injured by the rain. Over hill and down dale the kuruma road leads to Ureshino, a place celebrated for its mineral springs and bath. On the way one passes through charming little ravines, where tiny cataracts come tumbling down the sides of moss-grown precipices, a country of pretty thatched cottages, temples, groves, and purling rivulets.

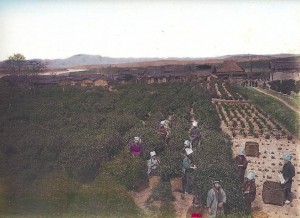

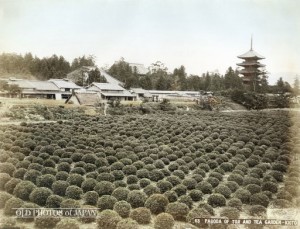

The gravelly hills about Ureshino are devoted to the cultivation of tea; the green tea-gardens, with the undulating, even rows of thick shrubs, looking very beautiful where they slope to the foot of the bare rocky cliffs. […]

[…]

The country hereabout is rich and populous, and the people seemingly well-to-do. The tea-houses, farm-houses, and even the little ricks of rice seem built with an eye to artistic effect. […] Passing through a mile or more of Saga’s smooth and continuously ridable streets, past big school-houses where hundreds of children are reciting aloud in chorus, past the big bronze Buddha for which Saga is locally famous, the road continues through a somewhat undulating country, ridable, generally speaking, the whole way. Long cedar or cryptomerian avenues sometimes characterize the way. […]

[…]

In every town and village one is struck with the various imitations of European goods. Ludicrous mistakes are everywhere met with, where this serio-comical people have attempted to imitate name, trade-mark, and everything complete. […]

[…]

[…] Today I pause a while before the public school in Nakabairu, watching the interesting exercises going on. Under the supervision of teachers in black frock-coats and Derby hats, a class of girls are ranged in two rows, throwing and catching pillows, altogether back and forth at the word of command. Classes of boys are manipulating wooden dumb-bells and exercising their muscles by various systematic exercises. The youngsters are enjoying it hugely, […] I suspect the Japanese children are about the only children in the wide, wide world who really enjoy studying their lessons and going to school. One of the teachers comes to the gate and greets me with a polite bow. I address him in English, but he doesn’t know a word.

[…] Today I pause a while before the public school in Nakabairu, watching the interesting exercises going on. Under the supervision of teachers in black frock-coats and Derby hats, a class of girls are ranged in two rows, throwing and catching pillows, altogether back and forth at the word of command. Classes of boys are manipulating wooden dumb-bells and exercising their muscles by various systematic exercises. The youngsters are enjoying it hugely, […] I suspect the Japanese children are about the only children in the wide, wide world who really enjoy studying their lessons and going to school. One of the teachers comes to the gate and greets me with a polite bow. I address him in English, but he doesn’t know a word.

The wooden houses of Japan seem frail and temporary, but they look new and bright mostly in the country. […] The roads, too, are sometimes laid out straight and trim, suggestive of an attempt to imitate the roads of France; then, again, one traverses for miles the counterpart of the green lanes of Merrie England—narrow, winding, and romantic. […]

[…]

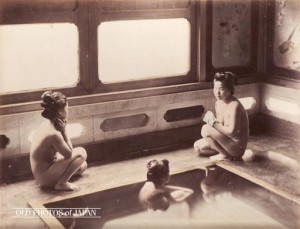

Following for some distance along the bank of a large canal I reach the village of Hakama for the night. The yadoya here is simply spotless from top to bottom; however the Japanese hotel-keeper manages to transact business and preserve such immaculate apartments is more of a puzzle every day. The regulation custom at a yadoya is for the newly arrived guest to take a scalding hot bath, and then squat beside a little brazier of coals, and smoke and chat till supper-time. The Japanese are more addicted to hot-water bathing than the people of any other country.  They souse themselves in water that has been heated to 140 deg. Fahr., a temperature that is quite unbearable to the “Ingurisu-zin” or “Amerika-zin” until he becomes gradually hardened and accustomed to it. Both men and women bathe regularly in hot water every evening.Following for some distance along the bank of a large canal I reach the village of Hakama for the night. The yadoya here is simply spotless from top to bottom; however the Japanese hotel-keeper manages to transact business and preserve such immaculate apartments is more of a puzzle every day. The regulation custom at a yadoya is for the newly arrived guest to take a scalding hot bath, and then squat beside a little brazier of coals, and smoke and chat till supper-time. The Japanese are more addicted to hot-water bathing than the people of any other country. They souse themselves in water that has been heated to 140 deg. Fahr., a temperature that is quite unbearable to the “Ingurisu-zin” or “Amerika-zin” until he becomes gradually hardened and accustomed to it. Both men and women bathe regularly in hot water every evening. […]

They souse themselves in water that has been heated to 140 deg. Fahr., a temperature that is quite unbearable to the “Ingurisu-zin” or “Amerika-zin” until he becomes gradually hardened and accustomed to it. Both men and women bathe regularly in hot water every evening.Following for some distance along the bank of a large canal I reach the village of Hakama for the night. The yadoya here is simply spotless from top to bottom; however the Japanese hotel-keeper manages to transact business and preserve such immaculate apartments is more of a puzzle every day. The regulation custom at a yadoya is for the newly arrived guest to take a scalding hot bath, and then squat beside a little brazier of coals, and smoke and chat till supper-time. The Japanese are more addicted to hot-water bathing than the people of any other country. They souse themselves in water that has been heated to 140 deg. Fahr., a temperature that is quite unbearable to the “Ingurisu-zin” or “Amerika-zin” until he becomes gradually hardened and accustomed to it. Both men and women bathe regularly in hot water every evening. […]

[…]

[…] from Kokura one can look across the narrow strait and see Shimonoseki, on the mainland of Japan. Thus far we have been traversing the island of Kiushiu, separated from the main island by a strait but a few hundred yards wide at Shimonoseki. […]

[…] from Kokura one can look across the narrow strait and see Shimonoseki, on the mainland of Japan. Thus far we have been traversing the island of Kiushiu, separated from the main island by a strait but a few hundred yards wide at Shimonoseki. […]

[…] Not content with merely copying an imported article, the Japanese artisan generally endeavors to make some improvement on the original. […]

A big Shinto temple occupies the crest of a little hill near by, and flights of stone steps lead up to the entrance. At the foot of the steps, and repeated at several stages up the slope, are the peculiar torii, or “bird-perches,” that form the distinctive mark of a Shinto temple. Numerous shrines occupy the court-yard of the temple; the shrines are built of wood mostly, and contain representations of the various gods to whose particular worship they are dedicated. Before each shrine is a barred receptacle for coins. The Japanese devotee poses for a minute before the shrine, bowing his head and smiting together the palms of his hands; he then tosses a diminutive coin or two into the barred treasury, and passes on […]

[…] Everybody is smiling and urbane, nobody looks serious; no careworn faces are seen, no pinched poverty. Wonderful people! they come nearer solving the problem of living happily than any other nation. […]

[…] Everybody is smiling and urbane, nobody looks serious; no careworn faces are seen, no pinched poverty. Wonderful people! they come nearer solving the problem of living happily than any other nation. […]

The architecture of the villages above Shimonoseki is strikingly artistic. The quaint gabled houses are painted a snowy white, and are roofed with brown glazed tiles of curious pattern, also rimmed with white. About the houses are hedges grotesquely clipped and trained in imitation of storks, animals, or fishes, miniature orange and persimmon trees, pretty flower-gardens and […]

[…]

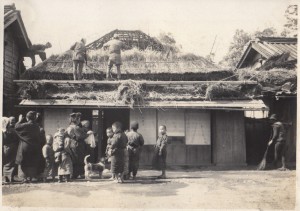

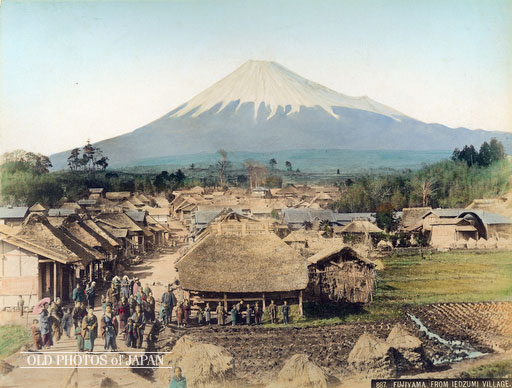

Most farm-houses are now thatched with straw; one need hardly add that they are prettily and neatly thatched, and that they are embellished by various unique  contrivances. Some of them, I notice, are surrounded by a broad, thick hedge of dark-green shrubbery. The hedge is trimmed so that the upper edge appears to be a continuation of the brown thatch, which merely changes its color and slopes at the same steep gradient to the ground. This device produces a very charming effect, particularly when a few neatly trimmed young pines soar above the hedge like green sentinels about the dwelling. One inimitable piece of “botanical architecture” observed today is a thick shrub trimmed into an imitation of a mountain, with trees growing on the slopes, and a temple standing in a grove. Before many of the houses one sees curious tree-roots or rocks, that have been brought many a mile down from the mountains, and preserved on account of some fanciful resemblance to bird, reptile, or animal. Artificial lakes, islands, waterfalls, bridges, temples, and groves abound; and at occasional intervals a large figure of the Buddha squats serenely on a pedestal, smiling in happy contemplation of the peace, happiness, prosperity, and beauty of everything and everybody around. Happy people! happy country. […]

contrivances. Some of them, I notice, are surrounded by a broad, thick hedge of dark-green shrubbery. The hedge is trimmed so that the upper edge appears to be a continuation of the brown thatch, which merely changes its color and slopes at the same steep gradient to the ground. This device produces a very charming effect, particularly when a few neatly trimmed young pines soar above the hedge like green sentinels about the dwelling. One inimitable piece of “botanical architecture” observed today is a thick shrub trimmed into an imitation of a mountain, with trees growing on the slopes, and a temple standing in a grove. Before many of the houses one sees curious tree-roots or rocks, that have been brought many a mile down from the mountains, and preserved on account of some fanciful resemblance to bird, reptile, or animal. Artificial lakes, islands, waterfalls, bridges, temples, and groves abound; and at occasional intervals a large figure of the Buddha squats serenely on a pedestal, smiling in happy contemplation of the peace, happiness, prosperity, and beauty of everything and everybody around. Happy people! happy country. […]

CHAPTER XX.

THE HOME STRETCH.

During the afternoon the narrow kuruma road merges into a broad, newly made macadam, as fine a piece of road as I have seen the whole world round. Wonderful work has been done in grading it from the low-lying rice-fields, up, up, up, by the most gentle and even gradient, to where it seemingly terminates, far ahead between high rocky cliffs. The picture of charming houses and beautiful terraced gardens climbing to the very upper stories of the mountains here beggars description; […]

During the afternoon the narrow kuruma road merges into a broad, newly made macadam, as fine a piece of road as I have seen the whole world round. Wonderful work has been done in grading it from the low-lying rice-fields, up, up, up, by the most gentle and even gradient, to where it seemingly terminates, far ahead between high rocky cliffs. The picture of charming houses and beautiful terraced gardens climbing to the very upper stories of the mountains here beggars description; […]

New sensations of astonishment await me as the upper portion of the smooth boulevard is reached, and I find myself at the entrance to a tunnel about five hundred yards long and thirty feet wide. The tunnel is lit up by means of big reflectors in the middle, shining through the gloom as one enters, like locomotive headlights. […]

[…] Much of the time my road practically follows the shore, and sometimes simply follows the windings and curvatures of the gravelly beach. Most of the low land near the shore appears to be reclaimed from the sea—low, flat-looking mud-fields, protected from overflow by miles and miles of stout dikes and rock-ribbed walls. Fishing villages abound along the shore, and for long distances a recent typhoon has driven the sea inland and washed away the road. Thousands of men and women are engaged in repairing the damages with the abundance of material ready to hand on the sloping granite-shale hills around the foot of which the roadway winds.

[…]

In this room is a wonderful brass-bound cabinet, suggestive of soul-satisfying household idols and comfortable private worship. During the evening I venture to open and take a peep in this cabinet to satisfy a pardonable curiosity as to its contents. My trespass reveals a little wax idol seated amid a wealth of cheap tinsel ornaments, and bits of inscribed paper. Before him sets an offering of rice, sake, and dried fish in tiny porcelain bowls.

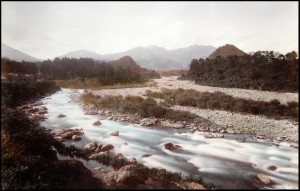

North of Hiroshima the country assumes a hilly character, the road following up one mountain-stream and down another.[…]

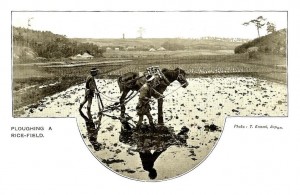

Among these mountains one is filled with amazement at the tremendous work the industrious Japs have done to secure a few acres of cultivable land. Dikes have been thrown up to narrow the channels of the streams, so that the remaining width of the bed may be converted into fields and gardens. The streams have been literally turned out of their beds for the sake of a few acres of alluvial soil. Among the mountains, chiefly between the mountains and the shore, are level areas of a few square miles, supporting a population that seems largely out of proportion to the size of the land. Many of these sea-shore people however, get their livelihood from the blue waters of the Inland Sea; fish sharing the honors with rice in being the staple food of provincial Japan.

The weather changes to quite a disagreeable degree of cold by the time I reach the end of to-day’s ride. This introduces me promptly into the mysteries of how the Japanese manage to keep themselves warm in their flimsy houses of wooden ribs and semi-transparent paper in cold weather. An opening in the floor accommodates a brazier of coals; over this  stands an open wood-work frame; quilts covered over the frame retain the heat. The modus operandi of keeping warm is to insert the body beneath this frame, wrapping the covering about the shoulders, snugly, to prevent the escape of the warm air within. The advantage of this unique arrangement is that the head can be kept cool, while, if desirable, the body can be subjected to a regular hot-air bath.

stands an open wood-work frame; quilts covered over the frame retain the heat. The modus operandi of keeping warm is to insert the body beneath this frame, wrapping the covering about the shoulders, snugly, to prevent the escape of the warm air within. The advantage of this unique arrangement is that the head can be kept cool, while, if desirable, the body can be subjected to a regular hot-air bath.

The following day is chilly and raw, with occasional skits of snow. People are humped up and blue-nosed, and seemingly miserable. Yet, withal, they seem to be only humorously miserable, and not by any means seriously displeased with the rawness and the snow. Straw wind-breaks are set up on the windward side of the tea-houses, and there is much stopping among pedestrians to gather around the tea-house braziers and gossip and smoke.

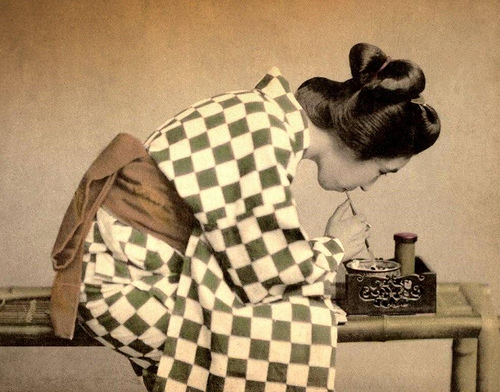

Everybody in Japan smokes, both men and women. The universal pipe of the country is a small brass tube about six inches long, with the end turned up and widened to form the bowl. This bowl holds the merest pinch of tobacco; a couple of whiffs, a smart rap on the edge of the brazier to knock out the residue, and the pipe is filled again and again, until the smoker feels satisfied. The girls that wait on one at the yadoyas and tea-houses carry their tobacco in the capacious sleeve-pockets of their dress, and their pipes sometimes thrust in the sash or girdle, and sometimes stuck in the back of the hair.

Everybody in Japan smokes, both men and women. The universal pipe of the country is a small brass tube about six inches long, with the end turned up and widened to form the bowl. This bowl holds the merest pinch of tobacco; a couple of whiffs, a smart rap on the edge of the brazier to knock out the residue, and the pipe is filled again and again, until the smoker feels satisfied. The girls that wait on one at the yadoyas and tea-houses carry their tobacco in the capacious sleeve-pockets of their dress, and their pipes sometimes thrust in the sash or girdle, and sometimes stuck in the back of the hair.

Many of the Buddhas presiding over the cross-roads and village entrances along my route to-day are provided with calico bibs, the object of which it is impossible for me to determine, owing to my ignorance of the vernacular. The bibs are, no doubt, significant of some particular season of religious observance.

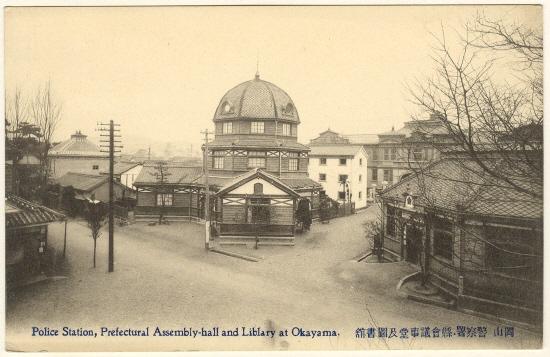

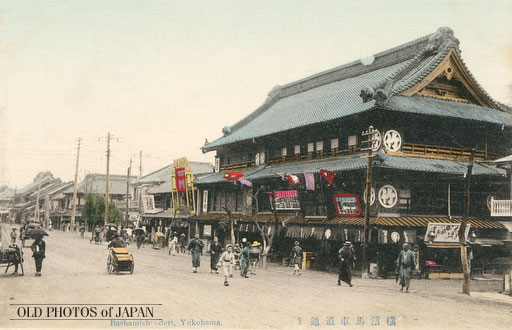

The important city of Okayama provides abundant food for observation—the clean, smooth streets, the wealth of European goods in the shops, and the swarms of ever-interesting people, as I wheel leisurely through it on Saturday, December 4th. […]

The important city of Okayama provides abundant food for observation—the clean, smooth streets, the wealth of European goods in the shops, and the swarms of ever-interesting people, as I wheel leisurely through it on Saturday, December 4th. […]

[…]

[…] I wheel away from Okoyama on Monday morning, passing through a country of rich rice-fields and numerous villages for some miles. The scene then changes into a beautiful country of small lakes and pine-covered hills, reminding me very much of portions of the Berkshire Hills, Mass. The weather is cool and clear, and the road splendid, although in places somewhat hilly.

Fifty-three miles are duly scored when, at three o’clock in the afternoon, I arrive at the city of Himeji. The yadoya here is a superior sort of a place, and Himeji numbers among its productions European pan (bread), steak, and bottled beer.  The Japs are themselves rapidly coming to an appreciation of this latter article, and even to manufacture it, a big brewery being already established somewhere near Tokio. A couple of young dandies of “New Japan” drop in during the evening, send out for bottles of beer, and seem to take particular delight in showing off their appreciation of the newly introduced beverage before their countrymen of the “ancient regime.”

The Japs are themselves rapidly coming to an appreciation of this latter article, and even to manufacture it, a big brewery being already established somewhere near Tokio. A couple of young dandies of “New Japan” drop in during the evening, send out for bottles of beer, and seem to take particular delight in showing off their appreciation of the newly introduced beverage before their countrymen of the “ancient regime.”

Beyond Himeji one leaves behind the mountains, emerging upon a broad, level, rice-producing plain, which extends eastward to Kobe and the sea-shore. The fine level road traversing the plain passes through numerous towns and villages, and for the latter half of the distance skirts the shore. Old dismantled stone forts, tea-houses, eating-stalls, fishermen’s huts, house-boats, and swarms of jinrikishas and pedestrians make their sea-shore road lively and interesting. The single artery through which the life of all the southern tributary country ebbs and flows to trade at the busiest treaty port in Japan, this road is constantly swarming with people.

Beyond Himeji one leaves behind the mountains, emerging upon a broad, level, rice-producing plain, which extends eastward to Kobe and the sea-shore. The fine level road traversing the plain passes through numerous towns and villages, and for the latter half of the distance skirts the shore. Old dismantled stone forts, tea-houses, eating-stalls, fishermen’s huts, house-boats, and swarms of jinrikishas and pedestrians make their sea-shore road lively and interesting. The single artery through which the life of all the southern tributary country ebbs and flows to trade at the busiest treaty port in Japan, this road is constantly swarming with people.  Over the Minato-gawa River by an elevated bridge, and one finds himself in a broad street leading through Hiogo to Kobe. These two cities are practically joined together, although bearing different names. Like many of the rivers of Japan, the bed of the Minato-gawa is elevated considerably above the surrounding plain. Confined between artificial banks to prevent the flooding of the adjacent fields in spring, the debris brought down from year to year has gradually raised the bed, and necessitated continued raising also of the levees. These operations have very naturally ended in raising the whole affair to an elevation that leaves even the bottom of the stream several feet higher than the fields around.

Over the Minato-gawa River by an elevated bridge, and one finds himself in a broad street leading through Hiogo to Kobe. These two cities are practically joined together, although bearing different names. Like many of the rivers of Japan, the bed of the Minato-gawa is elevated considerably above the surrounding plain. Confined between artificial banks to prevent the flooding of the adjacent fields in spring, the debris brought down from year to year has gradually raised the bed, and necessitated continued raising also of the levees. These operations have very naturally ended in raising the whole affair to an elevation that leaves even the bottom of the stream several feet higher than the fields around.

Kobe is one of the treaty ports of Japan, and nowadays is reputed to do more foreign trade than any of the others. One can imagine Kobe being a very pleasant and desirable place to live; the foreign settlement is quite extensive, the surroundings attractive, and the climate mild and healthful.

Pleasant days are spent at Kobe and Ozaka. Twenty-seven miles of level road from the latter city, following the course of the Yodo-gawa, a broad shallow stream that flows from Lake Biwa to the sea, brings me to Kioto. […]

Pleasant days are spent at Kobe and Ozaka. Twenty-seven miles of level road from the latter city, following the course of the Yodo-gawa, a broad shallow stream that flows from Lake Biwa to the sea, brings me to Kioto. […]

[…] Japanese mythology, religion, temples, politics, history, and titles, seem to me to be the worst mixed up and the most difficult for off-hand comprehension of anything I have yet undertaken to peep into. The multitudinous gods of the Hindoos, with their no less multitudinous functions, seem to me to be easily understood in comparison with the weird legends and mazy mythology of the Flowery Kingdom. Near this temple is a lovely little garden that gives much more satisfaction to the casual visitor than the temples. It is always a pleasure to visit a Japanese garden, and, in addition to its landscape attractions, historical interest lends to this one additional charm. The artificial lake is stocked with tame carp, which come crowding to the side when visitors clap their hands, in the expectation of being fed. […]

The one place I have been anticipating some real pleasure in visiting is the Shu-gaku-In gardens, one of the most famous gardens in this country where, above all others, gardening is pursued as a fine art. […]

[…]

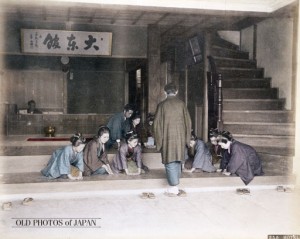

[…] One of the most curious scholarships of the place is the teaching of what is known as the “Japanese ceremony.” It seems to be a perpetuation of some old court ceremony of making tea for the Mikado. Expressing a wish to see the ceremony, I am conducted to a small room divided off by the usual sliding paper panels. A class of girls are kneeling in a row, confronting a very neat-looking old lady who sits beside a small brazier of coals. The old lady is the teacher; when she claps her hands, one of the paper screens slides gently aside and one of the scholars enters, bearing a small lacquer tray with tiny teapot and cups, a canister of tea, and various other paraphernalia. There is really very little to the “ceremony,” the graceful motions of the tea-maker being by far the more interesting part of the performance. The tea used is finely powdered and comes from Uji, where it is grown especially for the use of the Mikado’s household. The tea-dust is mixed with hot water by means of a curiously splintered bamboo mixer that looks very much like a shaving-brush. The result is a very aromatic cup of tea, delicious to the nostrils, but hardly acceptable to the European palate.

[…] One of the most curious scholarships of the place is the teaching of what is known as the “Japanese ceremony.” It seems to be a perpetuation of some old court ceremony of making tea for the Mikado. Expressing a wish to see the ceremony, I am conducted to a small room divided off by the usual sliding paper panels. A class of girls are kneeling in a row, confronting a very neat-looking old lady who sits beside a small brazier of coals. The old lady is the teacher; when she claps her hands, one of the paper screens slides gently aside and one of the scholars enters, bearing a small lacquer tray with tiny teapot and cups, a canister of tea, and various other paraphernalia. There is really very little to the “ceremony,” the graceful motions of the tea-maker being by far the more interesting part of the performance. The tea used is finely powdered and comes from Uji, where it is grown especially for the use of the Mikado’s household. The tea-dust is mixed with hot water by means of a curiously splintered bamboo mixer that looks very much like a shaving-brush. The result is a very aromatic cup of tea, delicious to the nostrils, but hardly acceptable to the European palate.

At Kioto begins the Tokaido, the most famous highway of Japan, a road that is said to have been the same great highway of travel, that it is to-day, for many centuries. It extends from Kioto to Tokio, a distance of three hundred and twenty-five miles.

Another road, called the Nakasendo, the “Road of the Central Mountains,” in contradistinction to the Tokaido, the “Road of the Eastern Sea,” also connects the old capital with the new; but, besides being somewhat longer, the Nakasendo is a hillier road, and less interesting than the Tokaido. After leaving the city the Tokaido leads over a low pass through the hills to Otsu, on the lovely sheet of water known as Biwa Lake.

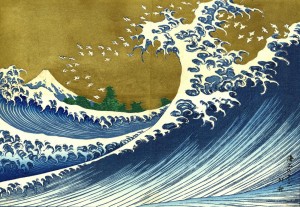

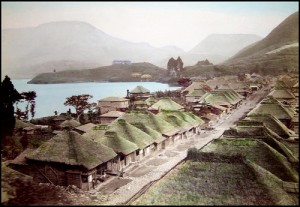

This lake is of about the same dimensions as Lake Geneva, and fairly rivals that Switzer gem in transcendental beauty. The Japs, with all their keen appreciation of the beauties of nature, go into raptures over Biwa Lake. Much talk is made of the “eight beauties of Biwa.” These eight beauties are: The Autumn Moon from Ishi-yama, the Evening Snow on Hira-yama, the Blaze of Evening at Seta, the Evening Bell of Mii-dera, the Boats sailing back from Yabase, a Bright Sky with a Breeze at Awadzu, Bain by Night at Karasaki, and the Wild Geese alighting at Katada. All the places mentioned are points about the lake. All sorts of legends and romantic stories are associated with the waters of Lake Biwa. Its origin is said to be due to an earthquake that took place several centuries before the Christian era; the legend states that Fuji rose to its majestic height from the plain of Suruga at the same moment the lake was formed. Temples and shrines abound, and pilgrims galore come from far-off places to worship and see its beauties.

This lake is of about the same dimensions as Lake Geneva, and fairly rivals that Switzer gem in transcendental beauty. The Japs, with all their keen appreciation of the beauties of nature, go into raptures over Biwa Lake. Much talk is made of the “eight beauties of Biwa.” These eight beauties are: The Autumn Moon from Ishi-yama, the Evening Snow on Hira-yama, the Blaze of Evening at Seta, the Evening Bell of Mii-dera, the Boats sailing back from Yabase, a Bright Sky with a Breeze at Awadzu, Bain by Night at Karasaki, and the Wild Geese alighting at Katada. All the places mentioned are points about the lake. All sorts of legends and romantic stories are associated with the waters of Lake Biwa. Its origin is said to be due to an earthquake that took place several centuries before the Christian era; the legend states that Fuji rose to its majestic height from the plain of Suruga at the same moment the lake was formed. Temples and shrines abound, and pilgrims galore come from far-off places to worship and see its beauties.

One object of special curiosity to tourists is a remarkable pine-tree, whose branches have been trained in horizontal courses over upright posts, until it forms a broad shelter over several hundred square yards. A smaller imitation of the large tree is also spreading to ambitious proportions on the Tokaido side.

Snow has fallen and rests on the upper slopes of the mountains overlooking the lake, little steamers and numerous sailing-craft are plying on the smooth waters, and wild geese are flying about. With these beauties on the left and tea-gardens on the right, the Tokaido leads through rows of stately pines, and past numerous villages along the lake shore.

Snow has fallen and rests on the upper slopes of the mountains overlooking the lake, little steamers and numerous sailing-craft are plying on the smooth waters, and wild geese are flying about. With these beauties on the left and tea-gardens on the right, the Tokaido leads through rows of stately pines, and past numerous villages along the lake shore.

The Nakasendo branches off to the left at the village of Kusa-tsu, celebrated for the manufacture of riding-whips. Through Ishibe and beyond, to where it crosses the Yokota-gawa, the Tokaido continues level a nd good. Near the crossing of this stream is a curious stone monument, displaying the carved figures of three monkeys covering up their eyes, mouth, and ears, to indicate that they will “neither see, hear, nor say any evil thing.” All through here the country is devoted chiefly to growing tea; very pretty the undulating ridges and rolling slopes of the broken foot-hills look, set out in thick, bushy, well-defined rows and clumps of dark, shiny tea-plants.

nd good. Near the crossing of this stream is a curious stone monument, displaying the carved figures of three monkeys covering up their eyes, mouth, and ears, to indicate that they will “neither see, hear, nor say any evil thing.” All through here the country is devoted chiefly to growing tea; very pretty the undulating ridges and rolling slopes of the broken foot-hills look, set out in thick, bushy, well-defined rows and clumps of dark, shiny tea-plants.

Down a very steep declivity, by sharp zigzags, the Tokaido suddenly dips into the little valley of the Yasose-gawa. At the foot of the hill is a curious shrine cave, containing several rude idols, a trough with tame goldfish, and one of the crudest Buddhas I ever saw. The aim of the ambitious sculptor of Buddhas is to produce a personification of “great tranquillity.” The figure in the Valley of Yasose-gawa is certainly something of a masterpiece in this direction; nothing could well be more tranquil than an oblong bowlder with the faintest chiselling of a mouth and nose, poised on the top of an upright slab of stone rudely chipped into a dim semblance of the human form.

A mile or two farther and my day’s ride of forty-six miles terminates at the village of Saka-no-shita. A comfortable yadoya awaits me here, no better nor worse, however, than almost every Jap village affords; but on the Tokaido the innkeepers are more accustomed to European guests than they are south of Kobe. Every summer many European and American tourists journey between Yokohama and Kobe by jinrikisha.

A mile or two farther and my day’s ride of forty-six miles terminates at the village of Saka-no-shita. A comfortable yadoya awaits me here, no better nor worse, however, than almost every Jap village affords; but on the Tokaido the innkeepers are more accustomed to European guests than they are south of Kobe. Every summer many European and American tourists journey between Yokohama and Kobe by jinrikisha.

At this yadoya I first become acquainted with that peculiar institution of Japan, the blind shampooer. Seated in my little room, my attention is attracted by a man who approaches on hands and knees, and butts his shaven pate accidentally against the corner of the open panel that forms my door. He halts at the entrance and indulges in the pantomime of pinching and kneading his person; his mission is to find out whether I desire his services. For a small gratuity the blind shampooer of Japan will rub, knead, and press one into a pleasant sensation from head to foot. This office is relegated to sightless individuals or ugly old women; many Japs indulge in their services after a warm bath, finding the treatment very pleasant and beneficial, so they say.

At this yadoya I first become acquainted with that peculiar institution of Japan, the blind shampooer. Seated in my little room, my attention is attracted by a man who approaches on hands and knees, and butts his shaven pate accidentally against the corner of the open panel that forms my door. He halts at the entrance and indulges in the pantomime of pinching and kneading his person; his mission is to find out whether I desire his services. For a small gratuity the blind shampooer of Japan will rub, knead, and press one into a pleasant sensation from head to foot. This office is relegated to sightless individuals or ugly old women; many Japs indulge in their services after a warm bath, finding the treatment very pleasant and beneficial, so they say.

[…]

The road averages good, although somewhat hilly in places, from Saka-no through lovely valleys and pine-clad mountains to Yokka-ichi. Yokka-ichi is a small seaport, whence most travellers along the Tokaido take passage to Miya in the steam passenger launches plying between these points. The kuruma road, however, continues good to the Kuwana, ten miles farther, whence, to Miya, one has to traverse narrower paths through a flat section of rice-fields, dikes, canals, and sloughs.

The road averages good, although somewhat hilly in places, from Saka-no through lovely valleys and pine-clad mountains to Yokka-ichi. Yokka-ichi is a small seaport, whence most travellers along the Tokaido take passage to Miya in the steam passenger launches plying between these points. The kuruma road, however, continues good to the Kuwana, ten miles farther, whence, to Miya, one has to traverse narrower paths through a flat section of rice-fields, dikes, canals, and sloughs.

A ri beyond Okabe and the pass of Utsunoya necessitates a mile or two of trundling. Here occurs a tunnel some six hundred feet in length and twelve wide; a glimmer of sunshine or daylight is cast into the tunnel by a system of simple reflectors at either entrance. These are merely glass mirrors, set at an angle to reflect the rays of light into the tunnel.

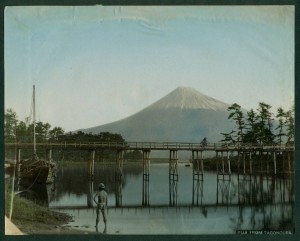

Descending this little pass the Tokaido traverses a level rice-field plain, crosses the Abe-kawa, and approaches the sea-coast at Shidzuoka, a city of thirty thousand inhabitants.  The view of Fuji, now but a short distance ahead, is extremely beautiful; the smooth road sweeps around the gravelly beach, almost licked by the waves. The breakers approach and recede, keeping time to the inimitable music of the surf; vessels are dotting the blue expanse; villages and tea-houses are seen resting along the crescent-sweep of the shore for many a mile ahead, where Fuji slopes so gracefully down from its majestic snow-crowned summit to the sea.

The view of Fuji, now but a short distance ahead, is extremely beautiful; the smooth road sweeps around the gravelly beach, almost licked by the waves. The breakers approach and recede, keeping time to the inimitable music of the surf; vessels are dotting the blue expanse; villages and tea-houses are seen resting along the crescent-sweep of the shore for many a mile ahead, where Fuji slopes so gracefully down from its majestic snow-crowned summit to the sea.

It is indeed a glorious ride around the crescent bay, through the sea-shore villages of Okitsu, Yui, Kambara, and Iwabuchi to Yoshiwara, a little town on the footstool of the big, gracefully sweeping cone. The stretch of shore hereabout is celebrated in Japanese poetry as Taga-no-ura, from the peculiarly beautiful view of Fuji obtained from it.

It is indeed a glorious ride around the crescent bay, through the sea-shore villages of Okitsu, Yui, Kambara, and Iwabuchi to Yoshiwara, a little town on the footstool of the big, gracefully sweeping cone. The stretch of shore hereabout is celebrated in Japanese poetry as Taga-no-ura, from the peculiarly beautiful view of Fuji obtained from it.

This remarkable mountain is the highest in Japan, and is probably the finest specimen of a conical mountain in existence. Native legends surround it with a halo of romance. Its origin is reputed to be simultaneous with the formation of Biwa Lake, near Kioto, both mountain and lake being formed in a single night—one rising from the plain twelve thousand eight hundred feet, the other sinking till its bed reached the level of the sea.

[…]

[…] Formerly an active volcano, Fuji even now emits steam from sundry crevices near the summit, and will some day probably fill the good people at Yoshiwara and adjacent villages with a lively sense of its power. Fuji is the special pride of the Japs, its loveliness appealing strongly to the national sense of landscape beauty. Of it their poet sings:

[…] Formerly an active volcano, Fuji even now emits steam from sundry crevices near the summit, and will some day probably fill the good people at Yoshiwara and adjacent villages with a lively sense of its power. Fuji is the special pride of the Japs, its loveliness appealing strongly to the national sense of landscape beauty. Of it their poet sings:

“Great Fujiyama, tow’ring to the sky. A treasure art thou, giv’n to mortal man, A god-protector watching o’er Japan: On thee forever let me feast mine eye.”

Fuji is passed and left behind, and sixteen miles reeled off from Yoshiwara, when Mishima, my destination for the night, is reached. A festival in honor of Oyama-tsumi-no-Kami, the god of “mountains in general,” is being held here; for, behold, today is November 15th, the “middle day of the bird,” one of the several festivals held in his honor every year. The big temple grounds are swarming with people, and pedlers, stalls, jugglers, and all sorts of attractions give the place the appearance of a country fair.

[…]

Down the street near my yadoya, within a boarded enclosure, a dozen wrestlers are giving an entertainment for a crowd of people who have paid two sen apiece entrance-fee. The wrestlers of Japan form a distinct class or caste, separated from the ordinary society of the country by long custom, that prejudices them against marrying other than the daughter of one of their own profession. As the biggest and more muscular men have always been numbered in the ranks of the wrestlers, the result of this exclusiveness and non-admixture with physical inferiors is a class of people as distinct from their fellows as if of another race. The Japanese wrestler stands head and shoulders above the average of his countrymen, and weighs half as much more. […]

Down the street near my yadoya, within a boarded enclosure, a dozen wrestlers are giving an entertainment for a crowd of people who have paid two sen apiece entrance-fee. The wrestlers of Japan form a distinct class or caste, separated from the ordinary society of the country by long custom, that prejudices them against marrying other than the daughter of one of their own profession. As the biggest and more muscular men have always been numbered in the ranks of the wrestlers, the result of this exclusiveness and non-admixture with physical inferiors is a class of people as distinct from their fellows as if of another race. The Japanese wrestler stands head and shoulders above the average of his countrymen, and weighs half as much more. […]

[…]

The one portion of the Tokaido impassable with a wheel commences at Mishima, the famous Hakone Pass, which for sixteen miles offers a steep surface of rough bowlder-paved paths. Coolies at Mishima make their livelihood by carrying goods and passengers over the pass on kagoa (the Japanese palanquin). Obtaining a couple of men to carry the bicycle, the chilly weather proves an inducement for following them afoot, rather than occupy a kago myself.[…]

The one portion of the Tokaido impassable with a wheel commences at Mishima, the famous Hakone Pass, which for sixteen miles offers a steep surface of rough bowlder-paved paths. Coolies at Mishima make their livelihood by carrying goods and passengers over the pass on kagoa (the Japanese palanquin). Obtaining a couple of men to carry the bicycle, the chilly weather proves an inducement for following them afoot, rather than occupy a kago myself.[…]

The country observed from the elevation of the Hakone Pass is extremely beautiful, the white-tipped cone of the magnificent Fuji towering over all, like a presiding genius. Near the hamlet of Yamanaka is a famous point, called Fuji-mi-taira (terrace for looking at Fuji). Big cryptomerias shade the broad stony path along much of its southern slope to Hakone village and lake.

The country observed from the elevation of the Hakone Pass is extremely beautiful, the white-tipped cone of the magnificent Fuji towering over all, like a presiding genius. Near the hamlet of Yamanaka is a famous point, called Fuji-mi-taira (terrace for looking at Fuji). Big cryptomerias shade the broad stony path along much of its southern slope to Hakone village and lake.

Hakone is a very lovely and interesting region, nowadays a favorite summer resort of the European residents of Tokio and Yokohama. From the latter place Hakone Lake is but about fifty miles distant, […] The lake is a most charming little body of water, a regular mountain-gem, reflecting in its clear, crystal depths the pine-clad slopes that encompass it round about, as though its surface were a mirror. […]

Hakone is a very lovely and interesting region, nowadays a favorite summer resort of the European residents of Tokio and Yokohama. From the latter place Hakone Lake is but about fifty miles distant, […] The lake is a most charming little body of water, a regular mountain-gem, reflecting in its clear, crystal depths the pine-clad slopes that encompass it round about, as though its surface were a mirror. […]

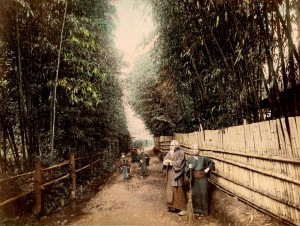

A magnificent avenue of cryptomeria shades the Tokaido for a short distance out of Hakone village; on the left is passed a large government sanitarium, one of those splendid modern-looking structures that speak so eloquently of the present Mikado’s progressive and enlightened policy. The road then turns up the steep mountain-slopes, fringed with impenetrable thickets of bamboo. Fuji, from here,  presents a grand and curious sight. The wind has risen, and the summit of the cone is almost hidden behind clouds of drifting snow, which at a distance might almost be mistaken for a steamy eruption of the volcano. Close by, too, the spirit of the wind moves through the bamboo-brakes, rubbing the myriad frost-dried flags together and causing a peculiar rustling noise—the whispering of the spirits of the mountains.

presents a grand and curious sight. The wind has risen, and the summit of the cone is almost hidden behind clouds of drifting snow, which at a distance might almost be mistaken for a steamy eruption of the volcano. Close by, too, the spirit of the wind moves through the bamboo-brakes, rubbing the myriad frost-dried flags together and causing a peculiar rustling noise—the whispering of the spirits of the mountains.

The summit reached, the Tokaido now leads through glorious pine-woods, descending toward the valley of the Sakawagawa by a series of breakneck zigzags. The region is picturesque in the extreme; a small mountain-stream tumbles along through a deep ravine on the left, mountains tower aloft on the other side, and here and there give birth to a cataract that tumbles and splashes down from a height of several hundred feet.

[…]

A fierce wind, blowing from the south, fairly wafts me along the last eleven miles of the Tokaido, from Totsuka to Yokohama. The wind, indeed, has been generally favorable since the rain-storm at Okabe, but it fairly whistles this morning. It calls to mind the Kansas wheelman, who claimed to have once spread his coat-tails to the breeze and coasted from Lawrence to Kansas City in three hours. Unfortunately I am wearing a coat the pattern of which does not admit of using the tails for sails otherwise the homestretch of the tour around the world might have provided one of the most unique incidents of the many I have encountered on the journey.

A fierce wind, blowing from the south, fairly wafts me along the last eleven miles of the Tokaido, from Totsuka to Yokohama. The wind, indeed, has been generally favorable since the rain-storm at Okabe, but it fairly whistles this morning. It calls to mind the Kansas wheelman, who claimed to have once spread his coat-tails to the breeze and coasted from Lawrence to Kansas City in three hours. Unfortunately I am wearing a coat the pattern of which does not admit of using the tails for sails otherwise the homestretch of the tour around the world might have provided one of the most unique incidents of the many I have encountered on the journey.

[…] And so the bicycle part of the tour around the world, which was begun April 22, 1884, at San Francisco, California, ends December 17, 1886, at Yokohama.

At this port I board the Pacific mail steamer City of Peking, which in seventeen days lands me in San Francisco. Of the enthusiastic reception accorded me by the San Francisco Bicycle Club, the Bay City Wheelmen, and by various clubs throughout the United States, the daily press of the time contains ample record. Here, I beg leave to hope that the courtesies then so warmly extended may find an echoing response in this long record of the adventures that had their beginning and ending at the Golden Gate.

At this port I board the Pacific mail steamer City of Peking, which in seventeen days lands me in San Francisco. Of the enthusiastic reception accorded me by the San Francisco Bicycle Club, the Bay City Wheelmen, and by various clubs throughout the United States, the daily press of the time contains ample record. Here, I beg leave to hope that the courtesies then so warmly extended may find an echoing response in this long record of the adventures that had their beginning and ending at the Golden Gate.

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/13749/pg13749.html

ok6xFIDFoO